Leigh Richmond Roose was a playboy sports star of the Edwardian era. Known as the Prince of Goalkeepers, he laid a trail of excellence for today's football icons to follow...

IT'S the transient nature of fame that a man once celebrated throughout the nation should vanish without trace and almost be forgotten.

Such was the fate of Leigh Richmond Roose, of Holt, in Wrexham, lauded in his lifetime as the Prince of Goalkeepers. He made his name and developed his unique playing style in the Edwardian era when soccer permitted tackles that today would justify a charge of grievous bodily harm.

Leigh's approach foreshadowed the role of the modern goalkeeper, turning him from the passive victim of charging centre-forwards to the aggressive custodian of the goal area.

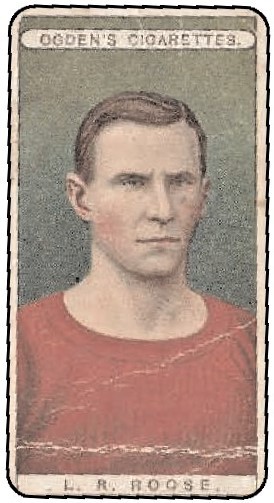

Leigh Richmond Roose on a cigarette card.

FA rules were different then, but his deliberate histrionics playing to the crowd and occasional mad moments remind us of at least half a dozen of today's finest goalkeepers.

The story of Leigh's remarkable life and mysterious death are told in Lost In France by Spencer Vignes, catching the sweaty heartbeat of many a forgotten football match in the 1890s and new century. It is also a story of how football developed into the favourite sport of masses.

Read more: Flintshire footballer Ron Davies had a head for success

Leigh was an inspirational figure for Stoke City, Sunderland and Wales, while also playing for Aston Villa, Arsenal and Everton. He was best mates with Billy Meredith, of Chirk, the man who first referred to him as the Prince of Goalkeepers.

Both came from North East Wales, today also famed for producing Ian Rush of Flint, Mark Hughes of Ruabon, and Michael Owen of Hawarden, among others.

Leigh pioneered the image of the sportsman celebrity, living it up in London, indulging his devoted female fans, at one time numbering saucy music hall star, Marie Lloyd, among his conquests.

Read more: Young Wrexham and Flintshire sports stars from the past

It all began when Leigh's father took over as minister of Holt Presbyterian Church in 1877. Holt in those days was notable for its boozy Sunday evening punch-ups as drinkers were attracted from the 'dry' counties of Denbighshire and Flintshire.

Leigh began school at Holt Academy, which once had H.G. Wells among its staff before he began his writing career. According to Vignes, Wells hated the village, later writing: "I knew I would have to escape from this flat, grey, desolate land, the dirty school and its Presbyterian habits.

"Holt turned out to be a squalid, ill-run travesty of the word Academy, boys slept three in a bed...and disorder threatened with such persistence the headmaster freely advocated in private the physical punishment he abhorred in public."

Read more: Remember T.E. Roberts? - "My dad wouldn’t buy tellies anywhere else!"

Wells also remarked on "the ordinate quantity of football to fill the gaps between learning".

Surely a failing much to Leigh Roose's liking. By the time he was 11 he was rarely seen without a football at his feet. He was drawn to the role of goalkeeper; a condition many regarded as madness.

Vignes puts it: "Goalkeepers were on a hiding to nothing. Largely unprotected by referees and regarded as cannon-fodder by outfield players who regularly used physical means to 'take out' the goalkeeper giving a team-mate the opportunity to score. Bones were broken, heads split and very occasionally someone died."

Read more: Buckley's town baths were an institution loved by generations

Leigh had his mind set on a medical career and was torn between studying and playing football. He compromised by remaining amateur and playing for expenses. At clubs like Stoke his expenses deals were so generous he was a professional in all but name, bending FA rules.

The talent he had shown playing around Wrexham was welcome when he went to University of Wales, Aberystwyth. He was the star of their team. He also discovered the pleasures of alcohol and flirting with girls. He was a showman or a show off, depending on your point of view.

Leigh wasn't always the darling of the crowd. Badly fouled in a match again Bangor campus, he lashed out a kick and sparked a brawl.

Read more: Remembering big fun at Wrexham Odeon big screen

During a post-match meal after a game between Sunderland and Stoke in 1906, a diner, thought to be the guest of a Sunderland director, called out insults to the Stoke players and would not be silenced. Leigh walked across and punched him in the face. The FA banned him from playing for 14 days.

In 1912, Leigh, the pin-up boy of Edwardian sport, had retired from top-flight football and was playing on a freelance basis in lower leagues.

He gave good entertainment, catching shots one-handed, performing acrobatics on crossbars and inviting spectators to take penalty kicks against him. He was in demand for shows and events where his popularity would draw crowds.

Read more: Football flashback as Wrexham match photo sparks nostalgic discussion

When he was called to arms in 1914 with the Royal Army Medical Corps, he was one of the first of the nation's sportsmen to do so. He witnessed dreadful carnage in Army field hospitals in France, before being recalled to take part in the Gallipoli campaign; another tragic slaughter.

In the summer of 1915, Leigh wrote to his Sunderland team-mate George Holley: "If ever there was a hell on this occasionally volatile planet then this oppressively hot, dusty, diseased place has to be it."

When Leigh's regular stream of letters dried up his family thought he might be among the casualties. No one seemed to know where he was - not even the RAMC.

Read more: "Loved it at Cranes" - Remembering where the music started for many

Then a chance remark by a journalist revealed Leigh had been playing cricket in Egypt after the Gallipoli evacuation.

Vignes suggests one reason for Leigh's apparent disappearance was an Army clerical error that changed his name from Roose to Rouse.

Fighting in France on the Somme, now with the Royal Fusiliers, Leigh won the Military Medal for outstanding courage. But it was in the chaos of war that the prince of goalkeepers vanished. His body was never found.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here