Ted Edwards and Gordon Prime are among the last surviving members of the ‘greatest generation’ which is remembered this weekend on the 77th anniversary of the D-Day landings.

Gordon, a motorcycle dispatch rider, was part of the giant force that stormed the beaches at Normandy on June 6, 1944, as the Allies sought to protect Europe from the clutches of Nazi tyranny.

Ted, who like Gordon served in the Royal Army Service Corp (RASC), landed in France a week later. Their units followed and supplied infantry soldiers cutting their way through Europe.

Both were teenagers who expected to serve their country in a war that had started years earlier and by June 1944 they were joining in the action they had been training for.

“You were called up when you were 18, nobody wants to go in the army in the wartime, but I had to accept it. I wasn’t bothered I had to go and that’s it,” said Ted, who grew up in Rhostyllen, a pit village near Wrexham, and who was an apprentice engineer when he enlisted in 1943.

Gordon, who now lives in Pembroke Dock, joined the Home Guard, with his First World War veteran father, in the West Midlands village he grew up in.

“We both joined and I said I was 17,” said Gordon who was actually a year younger than the minimum age for the home defence force when he volunteered shortly after war was declared in 1939.

“As soon as I became 18 I was called up. My pals had all joined different services and told me what a wonderful time they were having. I couldn’t wait to go but my mother said if I did (before I was 18) she would take my birth certificate (to the Army).”

Gordon, who had been riding motorcycles from the age of 11, hoped to be a dispatch rider in the Royal Corps of Signals but was sent to the RASC after the standard six weeks of infantry training.

He said: “I was told not to worry as they have dispatch riders too.”

In May 1944 Gordon’s unit was confined to Tilbury Docks, in London, loading ships: “We were briefed and paid in French money and set sail that night.

“We came down the Thames and the next morning the German guns from Calais opened up on us but missed, fortunately. When we got to the Isle of Wight we saw all the other ships.”

On D-Day Gordon first had to drive a three-tonne truck, packed with explosives, through three feet of water and onto Juno Beach. Then, as forces advanced, Gordon would weave his way on his motorbike back and fore to the frontline.

The realities of war were soon evident: “In the morning lots of French refugees passed us. We had these rations, including Nestle chocolate, which I didn’t like, and I gave it to these little French kids. I don’t think they’d seen chocolate before.”

In July Gordon would fire his revolver for the first time when his unit slept at a farm at Pont-l’Eveque: “There was an injured cow, full of maggots, lying on the ground and the farmer asked could I shoot it. I’d never shot anything before and I got my gun out but I didn’t kill it and had to try again."

As the army advanced France was being recaptured and old scores settled: “We stopped at one town square and there was a lot of commotion and they had got all these French girls lined up and were cutting all their hair off for collaborating with the Germans.”

Shortly before the end of the war, having reached Germany, Gordon’s friend Bert Stinchcome died during a regular run on his motorbike near Kevelaer – and it was down to chance that Gordon hadn’t been running the errand: “I had lost the toss of a coin and had to go back to the main headquarters.

“It should have been me on the run that night. That was 10 days before the end of the war. I lost six good pals and five in Normandy.”

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of VE Day, in 1995, Ted contacted the British Legion in his friend’s home village in Gloucestershire and visited to lay a wreath – with local residents also joining in the tribute.

“I’d never been but he always used to tell me about it,” said Gordon who has supported the Legion since leaving the army in 1947 and has been involved in Pembrokeshire since retiring to Tenby with his wife Patricia in 1988.

On Sunday’s 77th anniversary widower Gordon plans to lay a poppy wreath at the Normandy stone in Milford Haven and remember those lost in France and since: “There used to be 100 of us in Pembrokeshire but there’s only two left now.”

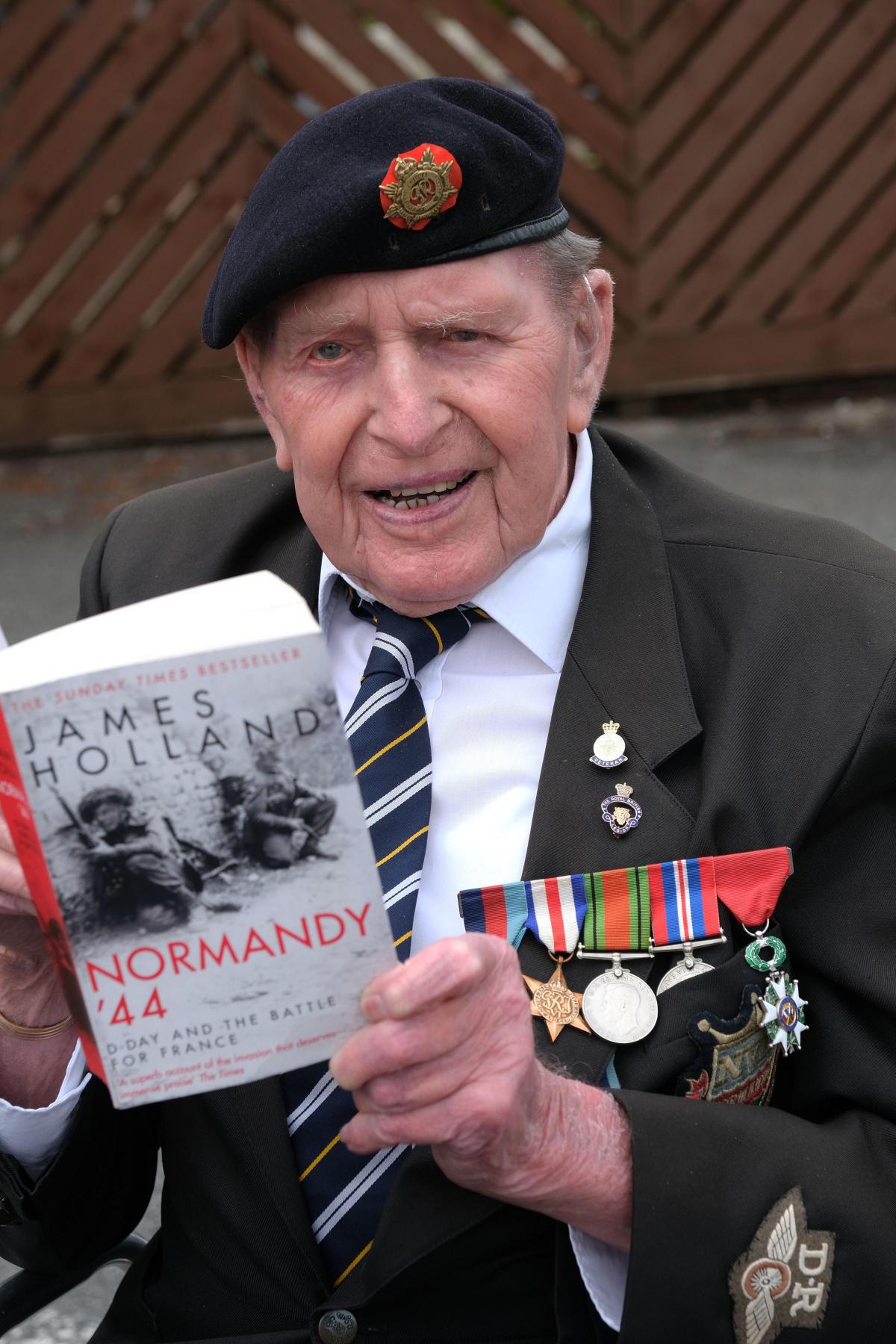

The camaraderie of Normandy veterans has always been important for 97-year-old Gordon. He formed a veterans group in the Midlands and returned to the battle sites for the first time to mark the 40th anniversary.

“When I first got home I think I had about three months paid leave and all my pals had come out of the services as well and we’d meet up every night and go to the pub. My mother used to say ‘Why don’t you stay in?’ but you couldn’t settle.

“Looking back I think we all suffered from PTSD. It wasn’t until I got married in 1953 that I could settle down. We’d all say the same – everyone drank about eight pints a night, terrible it was.”

Like Gordon, Ted served in the army until 1947 and when he was discharged set up home with his wife.

He has lived in Caia Park, Wrexham for the past 69 years and has supported other veterans through the Legion, including organising anniversary visits to Normandy – though he has never returned.

“I was chairman of the Normandy Veterans Association for 15 years but I think I’m the only one left now, there might be one or two others around Wrexham,” said the 96-year-old.

“I used to organise the trips for the association but I never went on them. The travel agent always used to ask ‘Why don’t you go?’ but I’d say I wasn’t interested. I’d rather not go back there and I didn’t want to be reminded of it.”

During the invasion Ted drove a truck, taking turns to sleep with his co-driver, as they raced to keep pace with the advancing forces and supply them with ammunition and petrol.

He said he would never let himself get carried away with thoughts of when the war would end.

“You never thought about that. You just thought about doing the job you had been trained to do. All other thoughts were out of your mind but you hoped it would be over quite soon. You were trained psychologically to just do the job and weren’t afraid of anything.

“You were always wary of being attacked from the air, it never happened – obviously.”

Ted, who remembers an uncle dying in the Gresford Colliery disaster which claimed 266 lives in 1934, also thinks the war brought about great social change.

He said: “When I was a boy we were very poor and the poor boys couldn’t try their 11-plus, I was one of them, and couldn’t afford the books.

“The only way you could afford to try was if your father had a professional job. It was a case of ‘them and us’, that’s how it was in those days.

“The war, in a way, did change that as we were all the same. It didn’t matter what education you had. I think things were a bit more even after the war, we had all served together and all fought, we were equal.”

On the anniversary Ted hopes to attend the service at the Normandy stone in Wrexham where he’ll honour those he fought alongside and those, including some schoolfriends, who didn’t return from the war.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here