FROM sharp force trauma to search dogs, Wrexham Glyndŵr University has been preparing students for an exciting career in forensic science for a number of years now.

The reputation of the BSc (Hons) Forensic Science degree at the university has gone from strength to strength, and the course is even responsible for Wales' only taphonomic facility, also known as a 'body farm', which uses pig carcasses and smaller animals to help students understand how remains decompose.

The site, alongside the dedicated crime scene house, enables students to be involved first-hand in research which aims to provide data which would help police with investigations particularly.

Students are trained in a wide variety of fields, including crime scene investigation, biology and chemistry and benefit from the university's long-term collaborations with partners, including North Wales Police, companies specialising in areas such as search dog training and the analysis of human remains, as well as analytical companies that provide students with opportunities to perform frontier research and publish papers.

"We work across universities in the UK hosting workshops on human identification and facial reconstruction," explains Dany Green, workshop coordinator and tutor with Yorkshire-based Sherlock Bone. "Travelling all over as I do, you learn about the different courses offering forensic science up and down the country, and there is a lot of really good stuff going on at this university, particularly around decomposition."

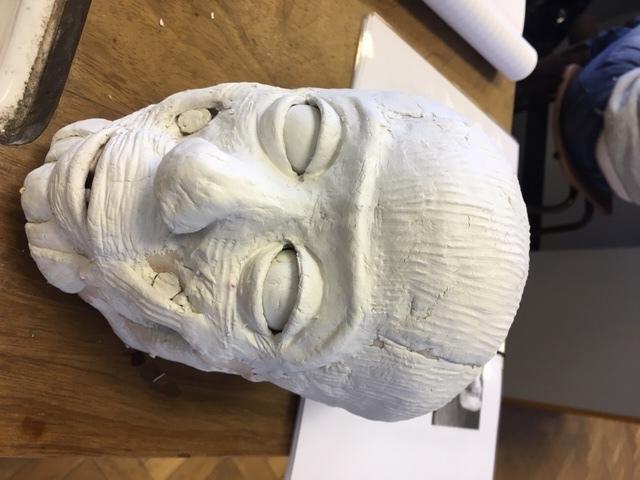

As I speak to her, Dany is using clay to reconstruct a skull's face. The process is eerie, as first muscle tissue, then features such as the eyes, nose and mouth are slowly and painstakingly added.

"We've been looking at some of the theory of forensic anthropology, such as features on the bone which can tell us things like ancestry and sex of an individual and then we use those characteristics to build up the muscles and put a face to the bone we're dealing with," says the university's programme leader in forensic science, Amy Rattenbury.

Facial reconstruction is a method used in the forensic field when a crime involves unidentified remains, whether they are skeletal or a body that is decaying.

"Quite often when a skeleton is recovered one of the triggers which can help people identify the remains is seeing a picture of what that individual might have looked like," continues Amy, whose specialism is in the technique of search, recovery and identification and she has substantive experience working with human skeletal remains. "If we're trying to determine the sex of an individual, we know that male skulls tend to be more robust with bigger, more angular muscles, and so we put pegs at different depths to be able to estimate the amount of muscle tissue which we build around the skull."

The degree students study for has been designed to provide a detailed knowledge of numerous scientific disciplines and how they can be applied to investigate a wide range of crimes and is tailored to train students to become competent and skilled scientists, able to conduct the analysis of materials, interpret complex results, and present their evidence as expert witnesses.

"We do a good mixture of different sciences and there is a lot of core chemistry where students learn about things, like testing suspect powders, drugs and toxicology analysis and anatomy, and of course we specialise in decomposition too, which is the really gory stuff!"

Glyndŵr's 'body farm', which is based in woods near the Wrexham campus, explores the ways in which animal remains decompose and is where Amy and her students monitor corpses and measure how they decay in different settings and temperatures.

"I specialise in decomposition and the search, recovery and identification of human remains," she explains. "The facilities here at the university are great, I can research and explore experiments that really interest me.

"The body farm is the first of its kind in Wales and there's very few in the whole of the UK. In America forensic scientists use human remains but it is still illegal in the UK, so we are still quite behind on the research."

The bodies are placed in a variety of areas; some will be buried in shallow graves, inside bags or hung up, and then left to rot while being monitored for decay.

Amy, who studied Forensic Biology at Staffordshire University and an MSc in Forensic Archaeology and Crime Scene Investigation at Bradford University, said: "We will look at how the surroundings affect decomposition, as usually a body is buried in a coffin, so we look at how this changes the way a human decomposes. The remains put in trees will be used to look at decomposition for scenarios such as air disasters and hangings.

"It isn't for the faint hearted but I don't think it is as morbid as some people assume it to be, and it is really important research in terms of identifying human remains and finding out how long someone has been dead for."

With forensic science playing an increasingly vital role in the criminal justice system and helping with the possibility of closure for distraught relatives, Amy is keen for people to understand the importance of her work

"The humanitarian aspect is the thing which often gets overlooked," she adds. "Ultimately the remains that we are dealing with belonged to somebody and sometimes that family doesn't necessarily know what happened to them, so the more information we can give them around an accurate identification when returning remains to loved ones, the better the world will be."

For more information on the BSc (Hons) Forensic course, visit www.glyndwr.ac.uk/en/Undergraduatecourses/ForensicScience/

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel