One families’ heartbreaking letters reveal the emotional ordeal of not knowing how their son was, only to discover he had succumbed to his injuries as the Armistice was signed.

FOR thousands of families who had suffered the loss of loved ones during the war, the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918 was a bittersweet occasion. Feelings of jubilation and relief that the fighting had ended were tempered by heartache and anguish at the terrible price that had been paid for peace.

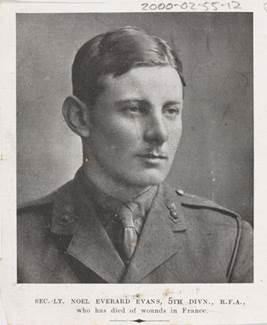

Noel Everard Evans was born on December 26, 1898, in Chirk, the son of the Reverend Enoch James Evans and his wife Violet Evans. Noel’s father was a vicar at St Trillo's Church at Llandrillo-yn-Rhos (Rhos on Sea) in Colwyn Bay. His grandfather, Major Thomas Everard-Hutton of the 4th Queen’s Own Light Dragoons, had been wounded in the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War (1854-56).

Noel was educated at Colet House School in Rhyl and Llandovery College. He excelled at sport, exhibiting such ability that, had it not been for the war, a professional career may well have been open to him. However, this was not to be. Like most young men of his generation, Noel was called upon to serve

Noel had arrived at the front in mid-September 1918. He was serving with 121st Battery in the 27th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, the unit in which his brother also served. By the time Noel arrived, this formation had been in almost continuous action since the German Spring Offensive of March 1918, and was now taking part in the Allied advance that took place after their victory at the Battle of Amiens in August. During his brief time in service, Noel and his comrades were frequently exposed to grave dangers and he survived several near misses.

On October 24, 1918, he wrote home: “We are at the moment halting, waiting for more orders. We often see the civilians of the towns, they look very ill, most of them. I have been having quite a thrilling time lately being chased by shells, but so far have been very lucky. I have got a piece of shrapnel that missed my cheek by a fraction of an inch and hit a wall beside me, so pocketed it and moved on.”

Noel’s luck finally ran out during the Battle of the Sambre. On November 4, 1918, a week before the hostilities ended, a shell burst a few yards from the dug-out where he was on duty. His commanding officer, Major L Bonner, 121st Battery, later wrote to his parents describing the events: “At about 6.30am, Noel went on duty and remained at the guns till 7.30am. Soon after this, at about 7.45am I should think, I was standing outside the dug-out and Noel walked towards me and we stood chatting for a few minutes; then I re-turned to the dug-out and had just stooped under the tarpaulin when a shell burst a few yards away. Our cook, who stood at the entrance of the dug-out, fell over on top of me, shot through the neck, and I was busy bandaging him when Noel was brought in. He appeared to be slightly wounded in the left thigh and right heel, and a tiny splinter was pulled out of the back of his head; his thigh seemed to worry him most, but the hit on the head had caused him to go temporarily blind: we put this down to concussion.”

Noel was evacuated to a hospital in the rear, while the Allied advance continued. Under relentless pressure, the Germans were eventually forced to sue for peace. At 5am on November 11, 1918, in a railroad carriage at Compiègne in France, the Allies signed an armistice with Germany. At 11am that day, the ceasefire came into effect, finally ending the war.

Desperate to find out what had happened to their son, Noel’s parents travelled to France to visit him in hospital. However, on arrival they were informed that their son had succumbed to his wounds in the early hours of Armistice Day. Although the recipient of this letter from his father, Reverend Enoch Evans, is unknown, it helps capture the tragedy with clarity and beauty: “It has been the hardest week to bear of my life... the uncertainty of the dear laddies’ condition. The suspense at the last moment when we reached the hospital and the crushing words of the matron “I’m afraid I have bad news for you”. We were too late. He had passed away on Monday morning in the early hours, strange to say just about the time the armistice was signed!...

"We reached the cemetery just in time. There were two other officers and about 20 privates buried at the same time. Noel was carried by five soldiers and five officers marched at the side… three volleys were fired and the “Last Post” sounded at the end. And there we have left our dear high-spirited laddie, who loved everybody and I believe was loved by all… It is such hard lines that he should have been taken at the very end of the war.”

Peace came at a huge price with 1918 the most devastating year on the Western Front. The mobile warfare since March had cost each side over a million men. Noel was buried in a cemetery near Rouen along with 30 of his comrades. Against the backdrop of the victory celebrations, his heart-broken family headed back to Britain to mourn, with his mother Violet Evans writing to her sister on November 16: “To think that we shall never see his dear smile again. It’s all been so cruelly hard... all the horrible noise and crowds and rejoicing everywhere day and night, it has been a continuous nightmare and the journey back I thought never would come to an end. It was such an awful shock when we got there to be told he had already gone to the cemetery… I don’t know how to face life without him.”

Noel was laid to rest in the St Sever Cemetery Extension at Rouen. A stained glass window was also erected in his memory at St George's Church, Llandrillo-yn-Rhos. The Evans family's collection of letters and photographs are now kept in National Army Museum, Royal Hospital Road, London, where they currently form part of the First World in Focus exhibition.

Entrance to the museum is free, with varying prices for special exhibitions.

Opening hours are: daily, 10am – 5.30pm, until 8pm first Wednesday each month and closed on 25, 26 December and 1 January

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here