ONE day, a small bundle of letters was found in a flea market in London. Written by a teenage boy, Percy to his girl, Kitty, they tell a tragic story of 1918 and of young people caught up in the horrors of the First World War.

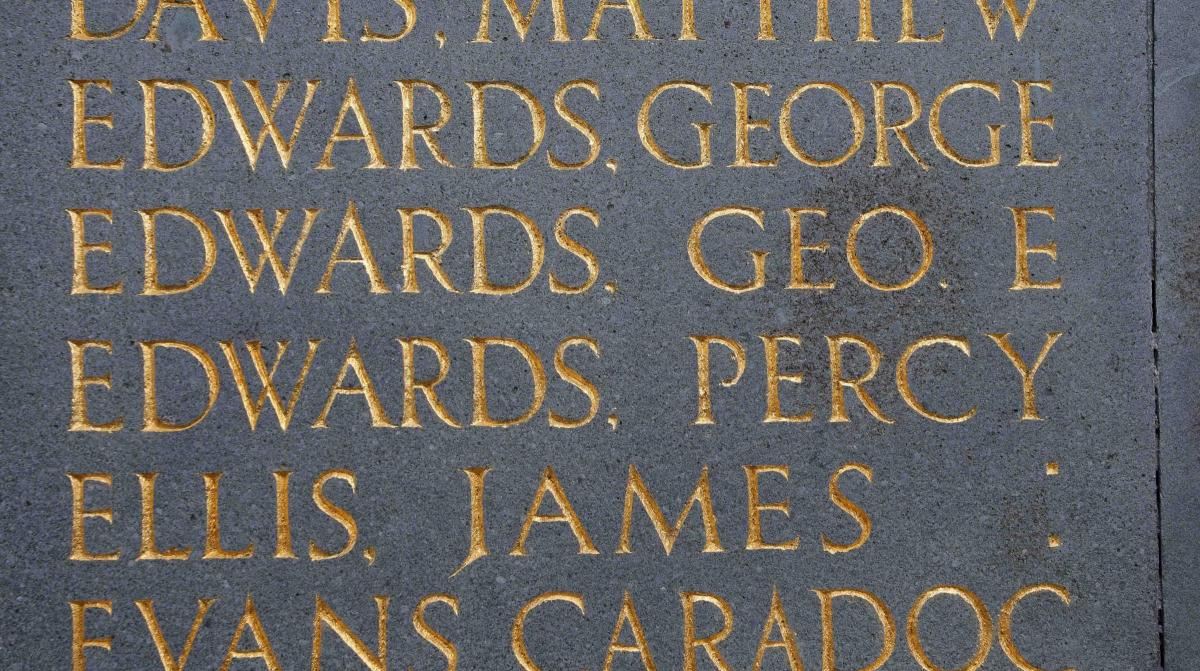

Like many teenagers in the the closing year of the war, Percy Edwards, who lived in Cefn Mawr, near Wrexham, was conscripted into the army and trained at Sniggery Camp near Liverpool, before he was sent to the front, aged just 18. Tragically, he was to die of his wounds three weeks after his arrival.

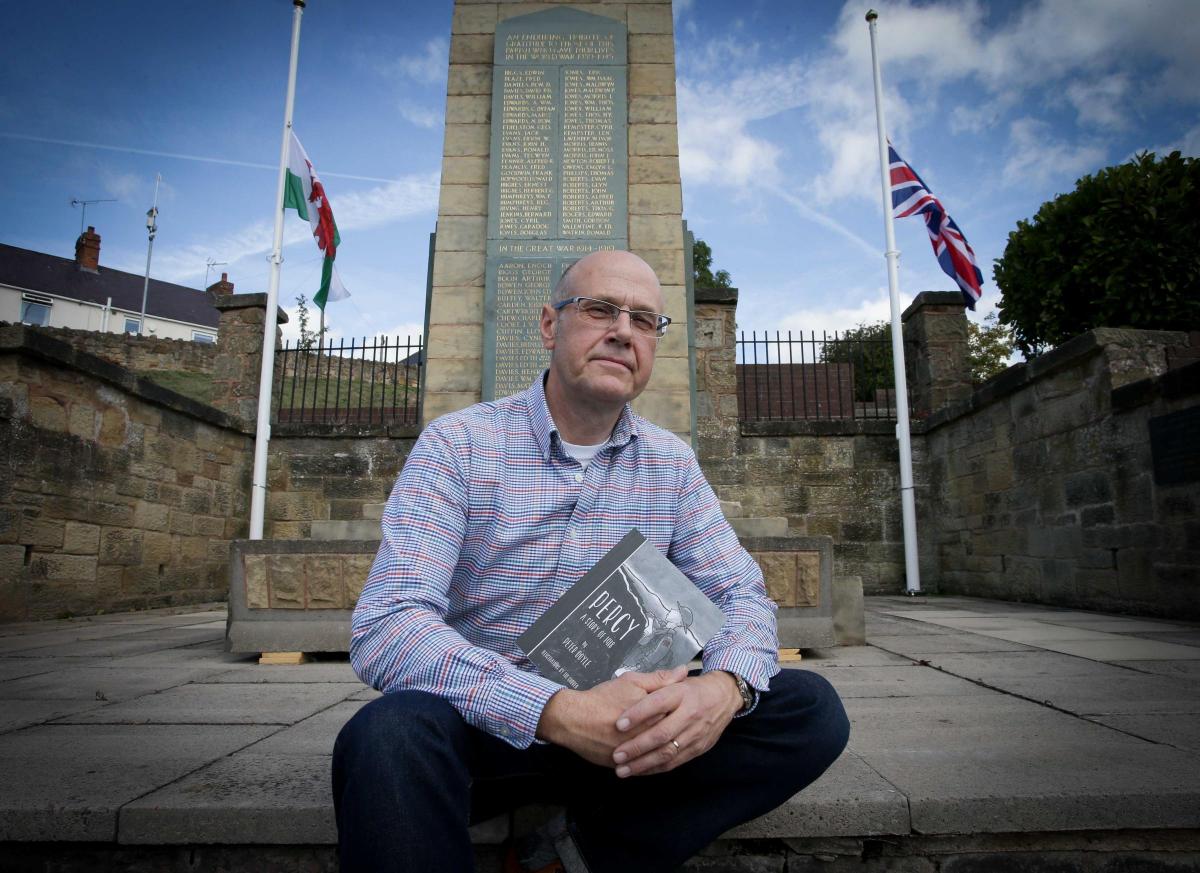

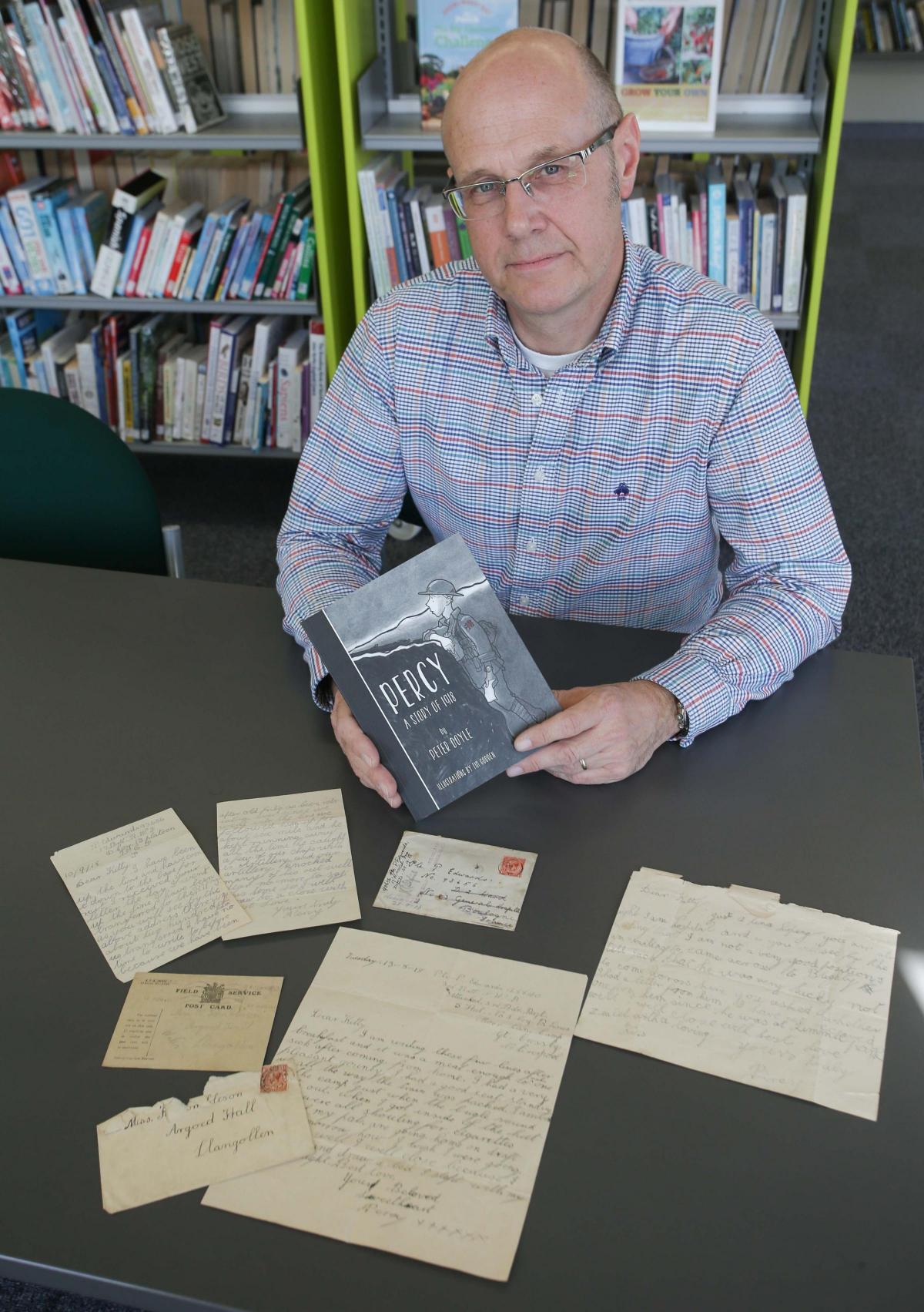

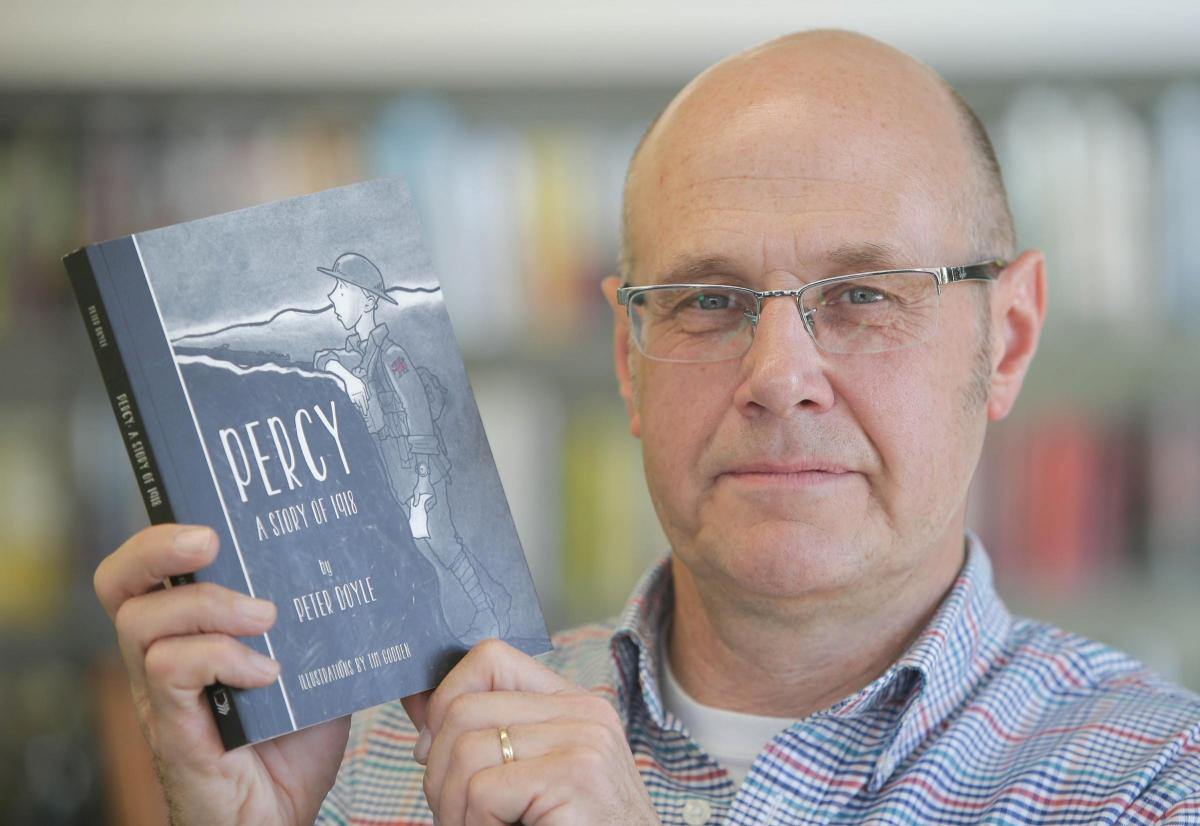

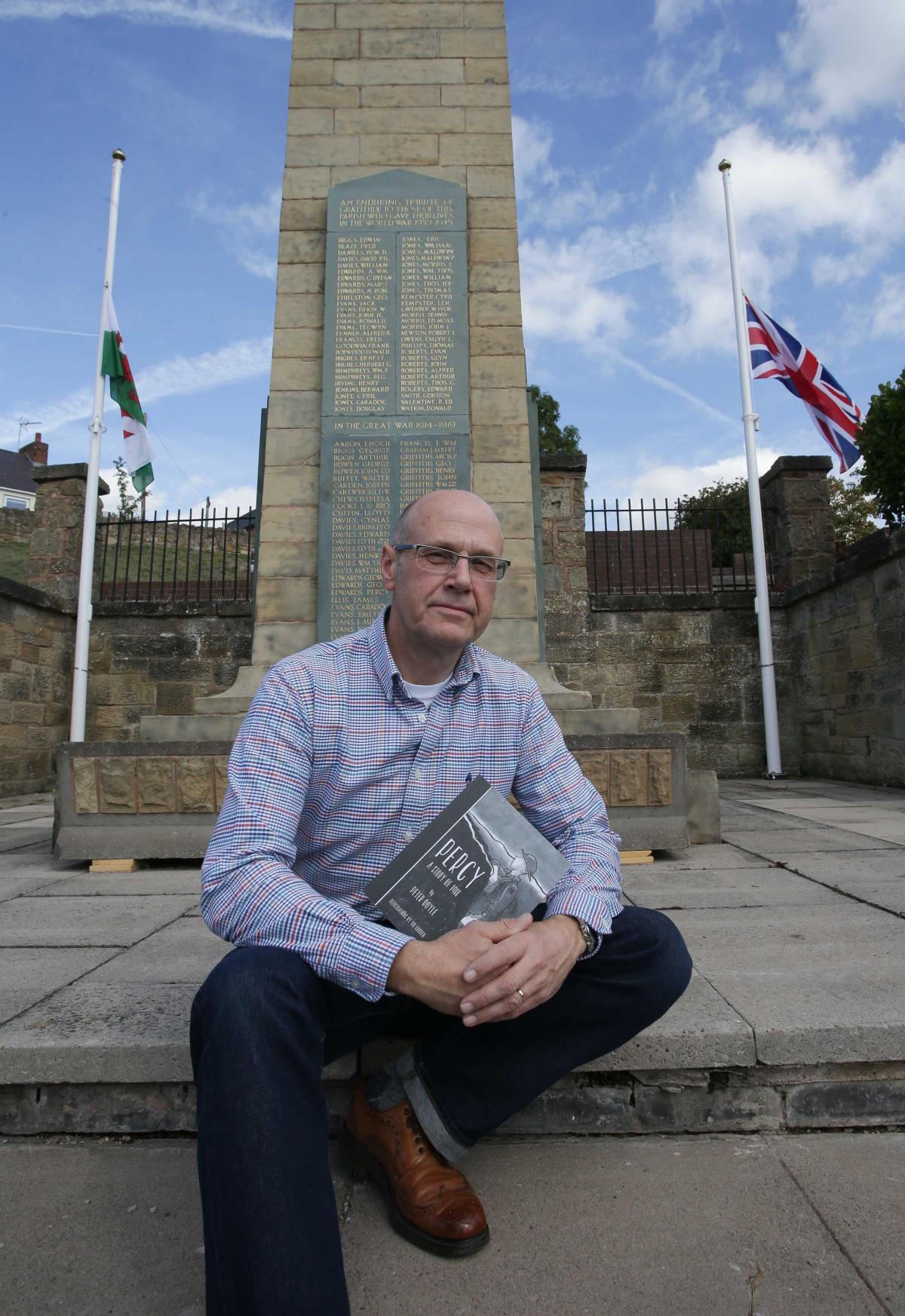

"I read a lot of communications from soldiers as part of my research," explains Professor Peter Doyle, who discovered the letters and used them as the inspiration for a new book for children about the First World War.

"But there was something different about these and they seemed special. I'm from Birkenhead and know North Wales well and they just struck a chord.

"Percy’s letters were few and his words sparse and immature, but they are very powerful. They had the feel of communications between a boyfriend and girlfriend today using social media."

Percy, who worked as pit worker, died from his wounds on September 28, 1918, and the centenary of his death was marked by Peter returning to the teenager's home town to give a talk to school children about his book and its subject's short life.

"Percy began his training in Formby from where he wrote regularly to Kitty Tombleson, who was a domestic servant from Froncysyllte," says Peter.

"I felt I needed to write an illustrated book that not only included the words from the letters but also pictures that showed the richness of the life he was about to go into," continues Peter, who is based at London's South Bank University.

Using Percy's letters along with surviving documents, war diaries, accounts of battles and newspaper cuttings, Peter gradually wrote Percy: A Story of 1918 which also uses illustrations by Tim Godden to tell the story of someone who the historian describes as an "everyman".

"It's an accurate picture of the war, the story of one soldier representing the bigger picture," he says. "What Percy brings is an authentic testimony of the final year of the Great war, through the eyes of one young man. Percy’s story is typical of the last year of the war, when the British Army fielded a conscript army of 18 year-olds and it is also a story of the contribution of

Wales to the Great War."

In July 1918, during his army training, a letter described how he and comrades were being taught to use their bayonets against the enemy.

"The man who can pull the ugliest face and do the most shouting is the best, so you can think what sort of a thing it is," he wrote.

In another letter, Percy revealed how a number of his comrades had fallen ill after being vaccinated against Typhoid fever, ahead of being deployed overseas.

"The chaps are fainting when they are on parade, but they don't get much sympathy here," he wrote. "Some chaps' arms have swollen so much that you can't see the shape of their elbows."

A month later Percy was transferred to the 17th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and was getting closer to the front.

"Dear Kitty, I have been up the line, and have now come back to the base for a rest."

In early September, he wrote: "I have had no time to write because we have been after old Fritz, who's been retiring ever since we went into the line.

"We followed him up for about six miles and he kept running away all the time.

"Fritz caught a few of our chaps with his artillery, and our artillery knocked many of his out," he wrote on September 10, 1918.

"Despite this being the closing stages of the war, the Germans were not by any means a spent force," says Peter, whose research has revealed Percy was mortally wounded after the Royal Welch Fusiliers came under artillery fire from "machine guns and hand grenades" while at the Somme.

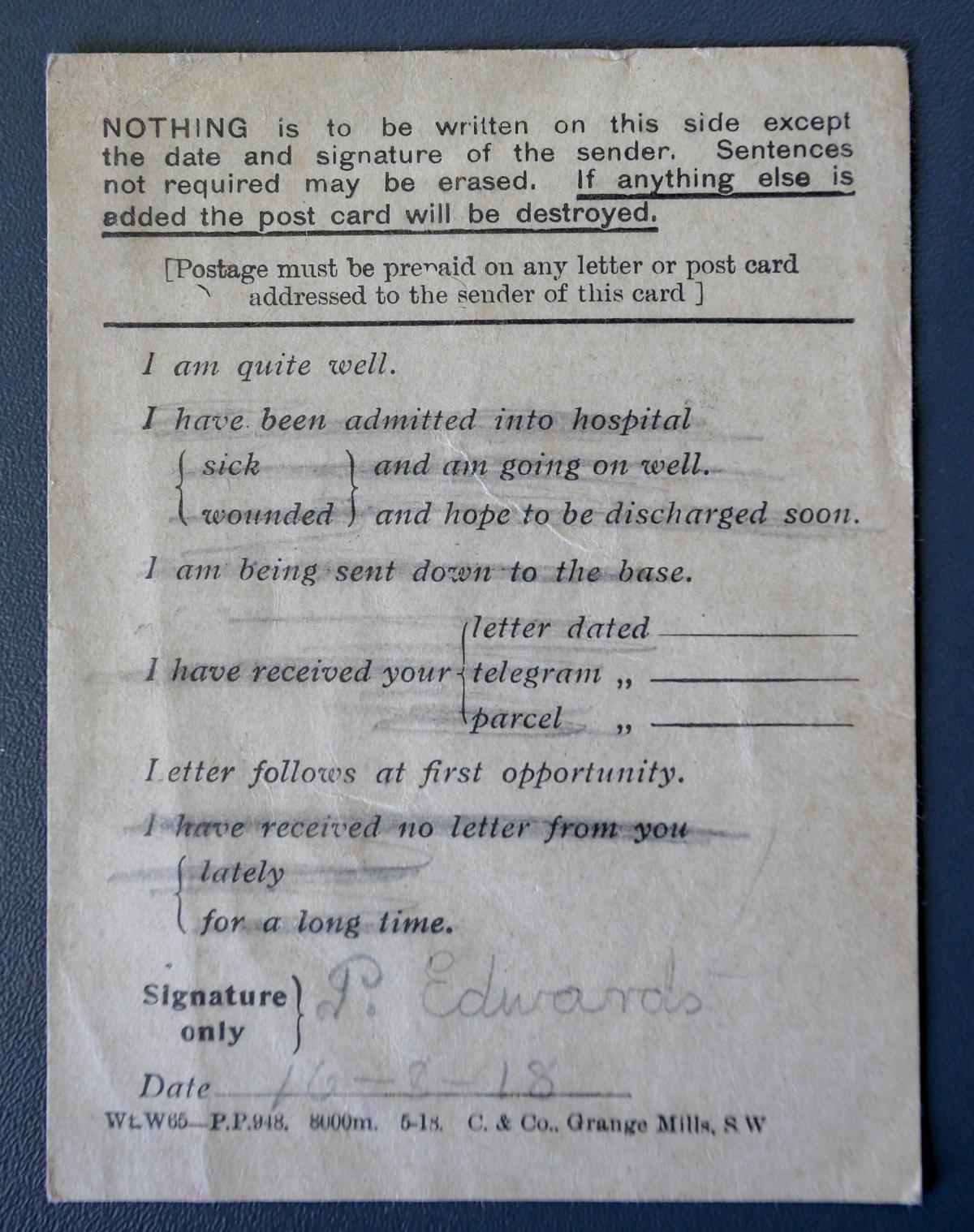

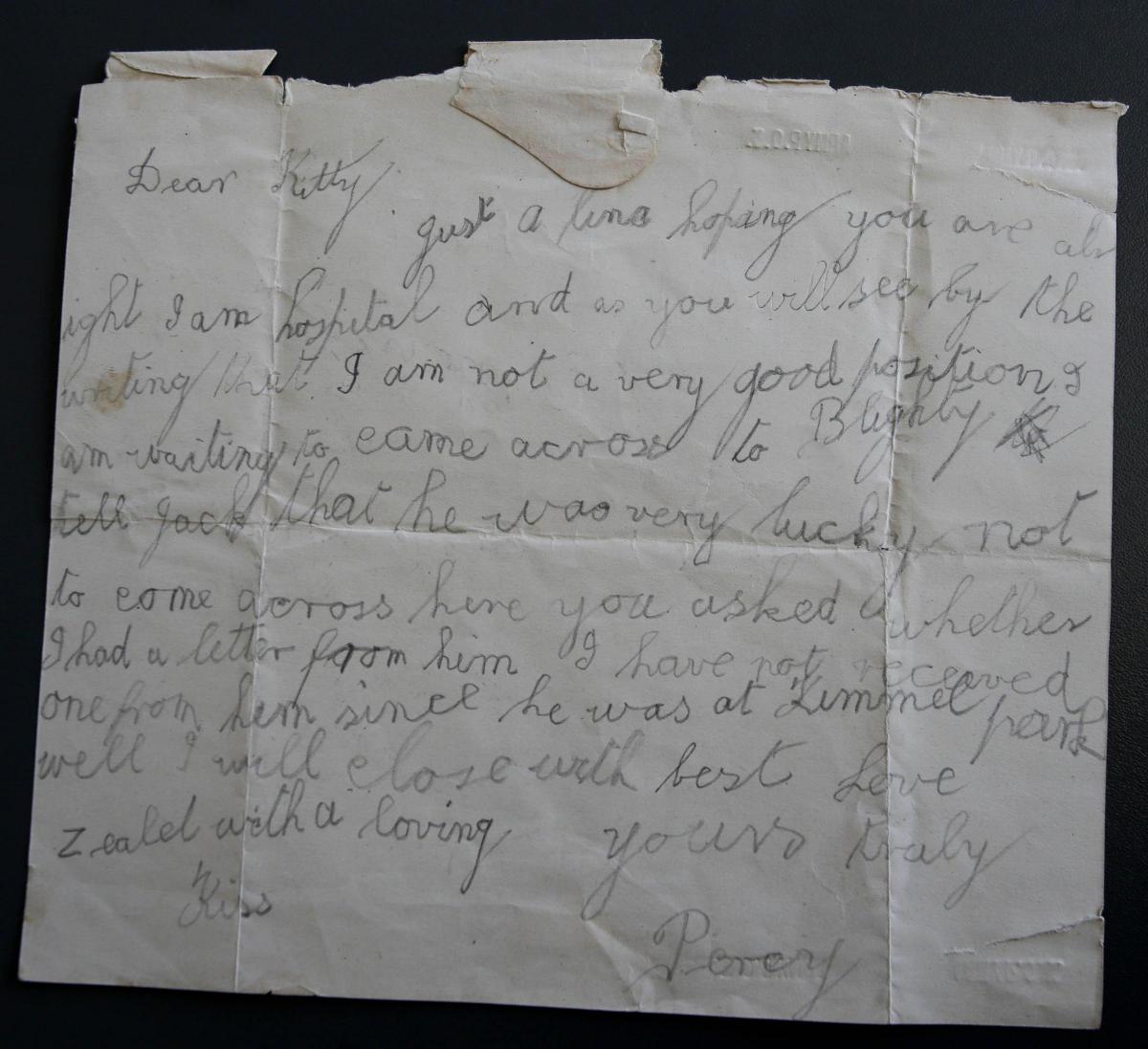

The teenager was transferred to a hospital in Boulogne from where he wrote a final letter to Kitty: "Just a line hoping you are all right. I am in hospital and, as you will see by the writing, that I am not in a very good position. I am waiting to come across to Blighty."

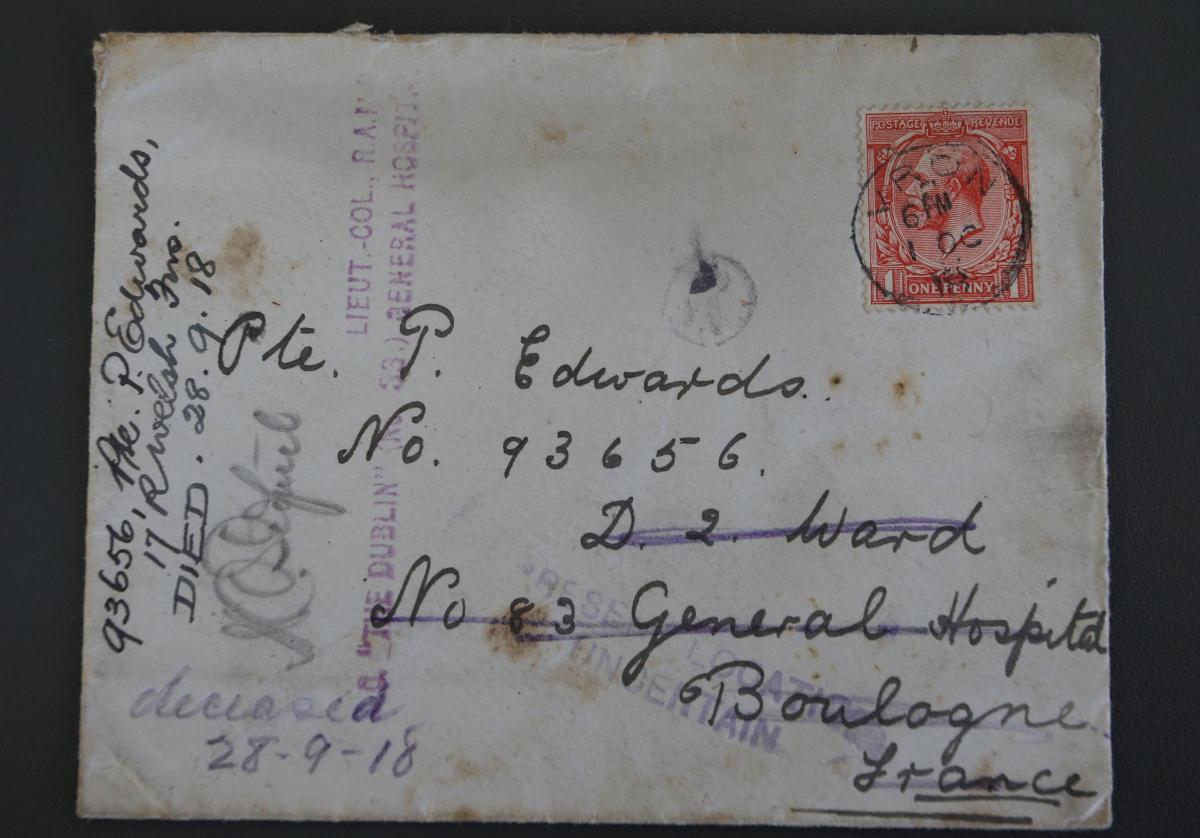

Tragically, Kitty must have believed her boyfriend would soon be home until one of her own letters addressed to him was eventually returned with the words "deceased" written on the front and the hospital address scribbled out.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records his grave at a cemetery at Terlincthun, near Boulogne.

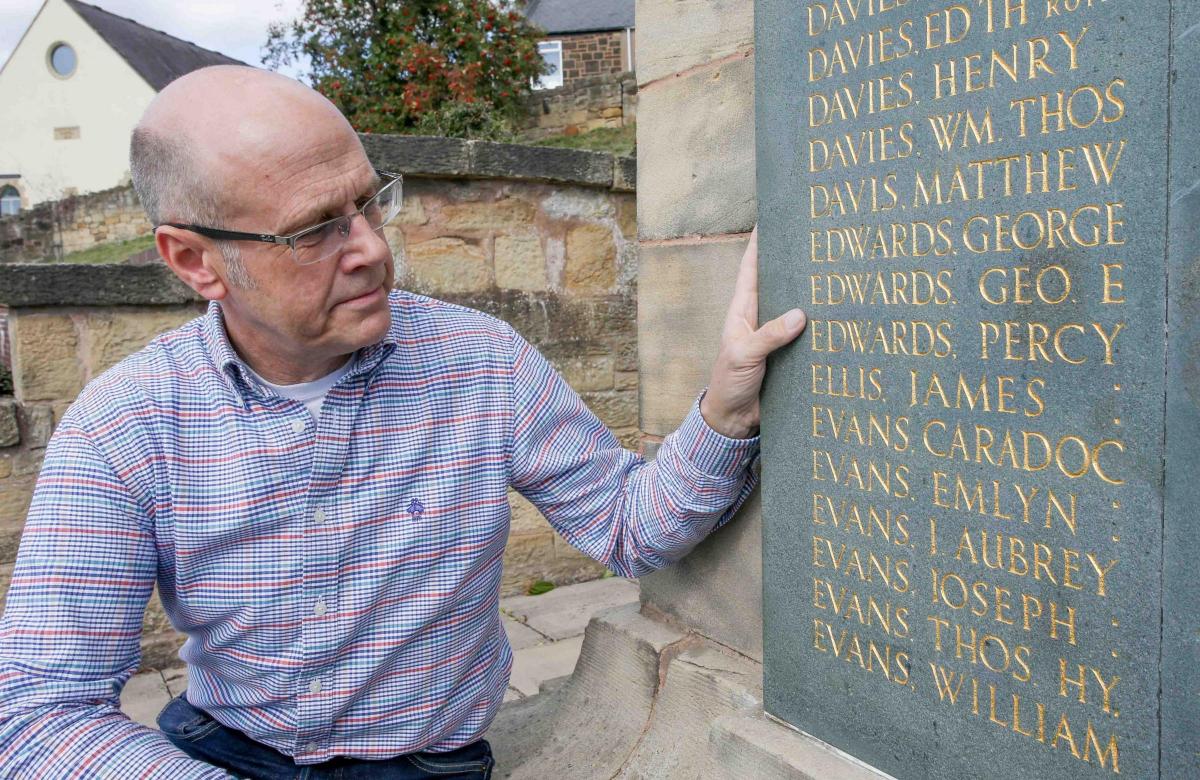

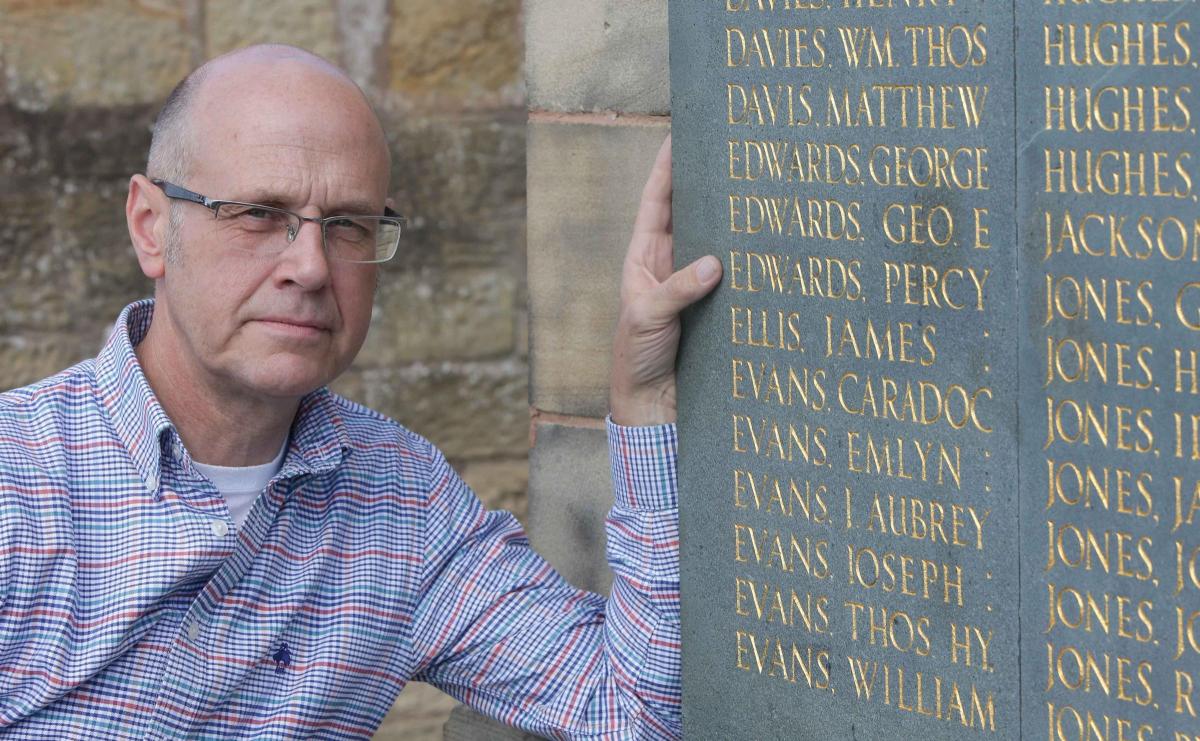

Peter visited Percy’s home village on the anniversary of his death, Friday, September 28, where he spoke to children from Cefn Mawr and Min y Ddol schools as well as addressing the local historical society at George Edwards Hall about how he came across the letters between Percy and his girl Kitty and then used them to bring Percy’s story to life.

The children in Cefn Mawr have spent the last 12 months researching the names of 130 local men, including Percy's, which are inscribed on their community's cenotaph.

"Percy's story is one I thought was very special," adds Peter. "It's become incredibly important to me."

Percy: A Story of 1918 is published by Uniform

P

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here